2: 4 95

KKU Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (Graduate Studies) Vol. 9 No.: 2May-August 2021

Implementing English-medium Instruction (EMI) in Thailand:

University Students’ Perspectives

Tang Keow Ngang

1

*

(Received: May 12, 2020; Revised: June 23, 2020; Accepted: September 10, 2020)

ABSTRACT

This study aims to explore the perceptions of higher education students concerning English as a medium of

instruction for teaching international programs at one of the public universities in Thailand. A total of 128 students

were selected from six programs participated in the current study using a stratified random technique. They completed

a self-assessment questionnaire about their experiences on their English academic skills as the impacts of EMI courses.

A survey method was employed using descriptive and inferential statistics to analyze the quantitative data generated.

The descriptive results indicated that students possessed the highest proficiency in reading skills (mean score = 3.30).

This is followed by writing skills (mean score = 2.77) and interactional skills (mean score = 2.72). Moreover, one-way

ANOVA showed a significant difference in reading and writing skills. Finally, the three English academic skills showed

significant inter-correlations.

Keywords: English academic skills, English proficiency, Medium of instruction

1

Corresponding author: tangng@kku.ac.th

*Associate Professor, International College, Khon Kaen University

2: 4 96

KKU Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (Graduate Studies) Vol. 9 No.: 2May-August 2021

Introduction

English as a medium of instruction (EMI) is defined as the use of English to teach academic subjects in

countries where the majority of people do not speak English as their first language or mother tongue [1]. However,

such definitions will be problematic in East Asia because EMI is often considered as part of an agenda to improve

English proficiency. [2] mentioned that initial growth in EMI provision was in Europe where there were approximately

11 times more EMI programs in 2014 than in 2001. Moreover, China and Japan have seen significant growth where

their governments are actively promoting EMI at the higher education institutions in recent years, with the aims of both

attracting more international students while improving the English proficiency of their citizens and to develop an

English-speaking workforce [3]. The major key driving EMI in Thailand is due to global competitiveness and the need

to meet world challenges. Therefore, the educational response was to react to external pressures and attempted to find

the best institutional structure for its needs. Indeed, the Thai government effort has made English as the major second

language and encouraged more EMI programs in higher education institutions [4].

Although international programs in higher education have been conducted in English to increase the English-

medium environment, the great majority of students in Thailand still always use the Thai language in their daily

communication and educational instruction. Moreover, the Thai language is being used and remains the primary

medium of instruction at higher education institutions despite the growing dominance of English [4]. It is reported that

the international programs in Thailand higher education institutions had almost increased doubled the number from

2004 to 2008, a total of 465 and 884 respectively in Thai public and private higher education institutions. If classified

in terms of the level of study, an international master’s degree is the highest number as 350 programs, followed by a

bachelor’s degree as 296 programs, and a doctoral degree has 215 programs [5].

EMI is growing very fast particularly in higher education to teach university courses in English. The EMI

growth varies depending on the country and the move towards teaching in English comes at the grassroots level [6].

According to [7], English which originates its status as the world’s fundamental language has resulted in the prompt

broadening of English use throughout worldwide nations as an international language because of the global propagation

of English. Therefore, the development of EMI is of great interest to language policy researchers in an era of

globalization and internationalization thus it has become an important issue and very challenging [8]. In Thailand, EMI

has progressed at the higher education level from being a Thai-English bilingual teaching experience in well-developed

socio-economic areas to being utilized right across the nation in the past decade [9]. Concurrently, an English

curriculum prioritizing English for specific purposes (ESP) is also promoted based on the argument that it can well

prepare higher education students for their academic study and professional work [10]. Consequently, many

governments believe that EMI programs can improve higher education students’ English proficiency and result in a

workforce that is more fluent in English. This is because EMI provides a double benefit, namely knowledge of their

subject and English language skills. Ultimately, government and higher education students think that this will make

them more attractive in the global job market and increase the demand for EMI tremendously [6].

2: 4 97

KKU Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (Graduate Studies) Vol. 9 No.: 2May-August 2021

[11] stated that English language teaching in Thailand higher education institutions still need improvement

to produce more competent graduates and labors who are fully competitive in the ASEAN Economy Community and

wider international market because EMI is considered as a key mechanism to equip university graduates with

professional language skills and competency [12]. Moreover, past researchers [13, 14, 15, 16, 17] found that Thai

people still have less proficiency compared to other ASEAN member countries. This may be caused by Thailand’s lack

of direct colonial experience and the scarcity of an intra-functional role of English in the country [7]. Even though

English is the main foreign language taught in Thailand’s basic education for more than 10 years, [18] indicated that

the current curriculum of Thailand failed to produce human capital with sufficient English competence to meet the

employers’ requirements in general. As a result, English has developed from being a foreign or second language to the

language of academic disciplines, particularly for international programs at higher education in Thailand [19].

Literature review

Many countries where English is not the native language of the majority of the population are gaining

popularity in their higher education institutions by using EMI. For example, it has been reported that Scandinavia and

Netherlands in Europe have switched to English in teaching STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics)

courses. Likewise, in Asia such as China, Japan, and Malaysia are also using EMI to teach academic subjects in higher

education institutions. [20] introduced five factors that must be considered while implementing EMI in non-native

English countries, namely students’ attitudes and motivation towards EMI, students’ level of English language

proficiency, instructors’ level of English language proficiency, instructors’ ability to teach EMI courses effectively,

and institutional support for EMI.

Based on research results from the past researchers [21, 22, 23, 24, 25] have identified theories of language

proficiency in a second language can theoretically be classified into proficiency in four different skills, namely reading,

writing, speaking, and listening. This means that to be able to understand the extent to which students are proficient in

a second language, they should be proficient in these four mentioned skills. The literature review has revealed that less

proficient students in reading skills use fewer strategies such as speed, vocabulary, and word recognition, and use them

even less effective in their reading comprehension. Likewise, students who possess better reading skills are better

strategy users. They can monitor their reading comprehension, can adjust their reading rates, know their phonological

and structural properties, and can consider their objectives for reading [26]. Besides, [22] conceptualized the writing

skills as embrace consideration of features of language form and usage. Strong development of writing skills enables

students to write research articles or business correspondence. The literature review has shown that listening is a very

complex skill since it is passive and not easily observable. Therefore, listening skills require more than motivation

alone to improve. It is situational and as our listening purposes change, so does the degree to which students require

various listening competencies, particularly to second language students [26]. Moreover, speaking skill is not easy to

identify how many oral abilities to determine students’ language development and proficiency. Speaking skill is not

often tested overtly by past researchers because it is time-consuming, and it is therefore neglected.

2: 4 98

KKU Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (Graduate Studies) Vol. 9 No.: 2May-August 2021

[27] studied whether EMI has an impact on Chinese undergraduates’ English proficiency and affects their

learning and use of the English language. A cross-sectional of 136 undergraduates involved in the survey and 10 focal

undergraduates participated in interviews. Their results showed that there is no statistically significant effect of EMI

on English proficiency or affect in their English learning and use. However, their results showed that undergraduates

are satisfied with EMI and perceived necessity for EMI, with significant effects on their learning outcomes besides

increasing their study burden. Moreover, prior English proficiency was the strongest predictor of subsequent English

proficiency and English-related effect. Their results raise concerns about the quality of the focal English-medium

program and prior English proficiency as a crucial factor to improve their language learning and use of the English

language.

[28] aimed to explore the perceptions of higher education students and instructors regarding EMI for teaching

science courses in the United Arab Emirates. A total of 100 English as a Foreign Language students completed a self-

assessment questionnaire about the impact of EMI course-taking experiences on their English academic skills. Besides,

10 students and four instructors have participated in in-depth interviews. Their results revealed that the impact of EMI

on the students’ learning experiences is because of their varied educational and linguistic backgrounds. The majority

of instructors and students supported using EMI in science courses.

[10] examined subject teachers’ perceptions and practices and students’ motivation and needs in English

learning of the EMI program in China. They examined how EMI instruction was delivered by subject teachers and how

English learning should be facilitated through the assistance of ESP courses when students’ English proficiency was

inadequate. They collected data from nine classroom observations, three post-observation interviews, and a

questionnaire survey. Their results revealed that effective instruction was maintained by deploying pragmatic strategies.

However, the goal of promoting English attainment was underachieved because language teaching was not explicitly

observed. Subject teachers’ perceptions of EMI undermined potential students’ linguistic gains. Their results

contributed to the immediate educational context as increasing access to ESP delivery that is fine-tuned to the language

issues in the EMI classroom. Collaboration between subject and language specialists is beneficial to students’ learning

including their subject knowledge and language skills. ESP practitioners need to consider students’ communication

needs in their disciplines and address the limitations of the current EMI practices in higher education in China.

[3] explored language and academic skills support provision, and attitudes on EMI programs among the

international students in Japan and China. Their study was supplemented with data from their previous study [29] and

provided insights into how students were supported in different EMI programs, as well as staff and students’ perceptions

of the role of such support. Their results imply that EMI programs should be the responsibility of content instructors

and language specialists, and the extent to which content instructors should be responsible for helping higher education

students with academic English.

2: 4 99

KKU Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (Graduate Studies) Vol. 9 No.: 2May-August 2021

Objectives of the study

The pressing issues about EMI in higher education include instructors’ English competence, varied needs of

heterogeneous students, doubtful quality of learning materials, and a mismatch between what is needed in target

academic conditions and what is provided by available EMI courses [30]. EMI was planned to be capable of developing

an international perspective in higher education students, improving their English proficiency, and providing access to

innovative knowledge available in English. Therefore, the Ministry of Education of Thailand made the number of EMI

courses offered an important criterion in higher education assessment [16]. These spikey problems were led to the

current research objective to investigate the extent that EMI can bring about successful language learning and how EMI

teaching can better facilitate students in their academic study. Regarding achieving the study objective, the researcher

planned to study the students’ self-perceptions of their academic language skills with special emphasis on the course

content. More specifically, the researcher sought to explore students’ literacy and interactional skills problems while

they were studying the EMI courses as below:

(i) To identify the problems of students’ literacy skills, namely writing and reading skills while they are

studying EMI courses.

(ii) To identify the problems of students’ interactional skills in class, namely speaking and listening skills

while they are studying EMI courses.

(iii) To examine the differences between English academic skills and students’ demographic backgrounds.

(iv) To examine the inter-correlation between academic language skills.

Methodology

The researcher employed a survey questionnaire to collect quantitative data. The target population is all

students from four divisions, namely Business Administration, International Affairs, Tourism Management, and

Communication Arts in one of the international colleges in Thailand. The required sample size was 150 undergraduate

students as respondents using a stratified random sampling technique. The stratified random sampling that was involved

in the division of a population into a smaller group known as strata. The sample size of each strata was proportionate

to the population size of the strata when viewed against the entire population. Final samples were selected

proportionally from the different strata. This means that each strata has the same sampling fraction.

The researcher adapted a survey questionnaire from [28]’s research instrument. It consists of 19 items that

were administered to 150 respondents for collecting information on their self-perception about the problems that they

faced while they were studying EMI courses. This method benefits this study as it provides an excellent means of

measuring attitudes and orientations in a large population which can, therefore, be generalized to a larger population

[31]. Section A of the questionnaire was intended to gather information about respondents’ demographic factors,

namely nationality, program, and academic study year. Section B was comprised of three items to gauge the perceptions

of respondents’ writing skills. Section C consisted of five items to measure respondents’ reading skills. Finally, Section

2: 4 100

KKU Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (Graduate Studies) Vol. 9 No.: 2May-August 2021

D had eight items to obtain information about respondents’ interactional skills. To measure the respondents’ self-

perception, a four-point Likert scale was utilized, ranged from ‘disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’.

Pilot testing of the instrument was conducted to five experts and 30 undergraduate students who were studying

in an international program in other faculties. The five experts were asked to give suggestions and comments on the

validity of the instrument while the 30 undergraduate students were asked to respond to the questionnaire to test the

consistency of the instrument. It could be concluded that the instrument was reliable and good to use as the Cronbach

alpha value was 0.92. Revisions were made according to the feedback from the five experts. Descriptive statistic

including mean score and standard deviation while inferential statistic, namely one-way ANOVA and Pearson’s

correlation coefficients were employed to analyze the collected data.

Results

The results are presented according to the study objectives, which have been previously stated. A total of 150

questionnaires were distributed to respondents but only 128 of them were successfully collected, giving a response rate

as 85.3 percent. The results are presented according to respondents’ perceptions of their productive skills of literacy

and interactional skills based on EMI courses.

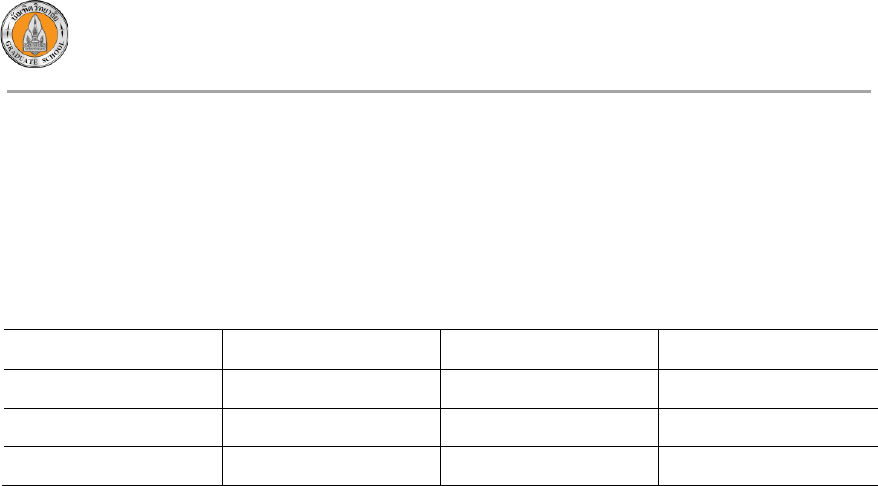

Descriptive results of literacy skills

Literacy skills consist of academic writing and reading skills. The results show how respondents perceived

their academic writing skills while they were studying in EMI courses. If the students’ perceptions are in the range of

‘agree’ to ‘strongly agree’, that means students do not have problems in their literacy skills. Table 1 shows 73.5%

(55.5% + 18.0%) of respondents reported that they are not having any problems to take notes in English. Besides,

73.4% (60.9% + 12.5%) of them do not encounter any problems to do their assignment in English, and 59.4% (50.8%

+ 8.6%) admit being at ease writing content-based English reports. Generally, most of the respondents 68.8% (55.7%

+ 13.1%) have a positive tendency toward writing skills parameters compared to 31.2% (4.9% + 26.3%) who do not.

The highest mean score was students’ ability in taking notes (𝑥̅ = 2.89; SD = 0.712). This is followed by their ability

in doing assignment in English (𝑥̅ = 2.81; SD = 0.707). The writing skills with the lowest mean score was writing a

report in English (𝑥̅ = 2.60; SD = 0.756).

2: 4 101

KKU Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (Graduate Studies) Vol. 9 No.: 2May-August 2021

Table 1 Academic writing skills

Writing skills

Disagree

Slightly

Disagree

Agree

Strongly

Agree

Mean

Score

S.D.

I find no difficulty taking notes in

English.

3 (2.3)

31 (24.2)

71 (55.5)

23 (18.0)

2.89

0.712

I find no difficulty doing an assignment

in English

6 (4.7)

28 (21.9)

78 (60.9)

16 (12.5)

2.81

0.707

I find no difficulty writing reports in

English

10 (7.8)

42 (32.8)

65 (50.8)

11 (8.6)

2.60

0.756

Collective ‘Writing’ construct

19 (4.93)

101 (26.3)

214

(55.73)

50 (13.03)

2.77

0.598

The descriptive analysis revealed that 66.4% (50.8% + 15.6%) of respondents perceive themselves as they do

not have difficulty in reading English textbooks and course materials. Nevertheless, a majority of respondents that are

71.1% (58.6% + 12.5%) who make an effort to do extra academic reading in English. Reading English books is claimed

not to be time-consuming by 55.5% (43.8% + 11.7%) of respondents, compared to 44.5% (11.7% + 32.8%) of

respondents who believe that reading in their mother tongue is more rapidly. Moreover, most of the respondents that

are 92.2% (51.6% + 40.6%) have confidence in reading academic materials that can improve their English vocabulary.

A total of 57.1% (39.1% + 18.0%) of respondents do extra readings that are unrelated to their studies. Taken as a whole,

68.46% (48.78% + 19.68%) of respondents express a positive attitude toward their English reading skills. Descriptive

results also indicated that the highest mean score in reading which can help them to expand their English vocabulary

(𝑥̅ = 3.31; SD = 0.661). This is followed by doing extra reading through textbooks and course materials (𝑥̅ = 2.81; SD

= 0.673), no problem in reading textbooks and course materials (𝑥̅ = 2.79; SD = 0.739), and reading English books

which are unrelated to their studies (𝑥̅ = 2.66; SD = 0.872). The least capacity of reading skills is respondents can read

in English faster than in their mother tongue (𝑥̅ = 2.55; SD = 0.849).

2: 4 102

KKU Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (Graduate Studies) Vol. 9 No.: 2May-August 2021

Table 2 Academic reading skills

Reading skills

Disagree

Slightly

Disagree

Agree

Strongly

Agree

Mean

Score

S.D.

I find no difficulty reading textbooks

and course materials.

4 (3.1)

39 (30.5)

65 (50.8)

20 (15.6)

2.79

0.739

I do the extra reading through

textbooks and course materials.

3 (2.3)

34 (26.6)

75 (58.6)

16 (12.5)

2.81

0.673

I do not feel reading in English is time

consuming compared to reading in the

mother tongue.

15 (11.7)

42 (32.8)

56 (43.8)

15 (11.7)

2.55

0.849

Reading textbooks and course

materials expands my English

vocabulary.

2 (1.6)

8 (6.3)

66 (51.6)

52 (40.6)

3.31

0.661

I read English books that are unrelated

to my studies.

11 (8.6)

44 (34.4)

50 (39.1)

23 (18.0)

2.66

0.872

Collective ‘Reading’ construct

35 (5.46)

167

(26.12)

312

(48.78)

126

(19.68)

3.30

0.842

Descriptive results of interactional skills

Interactional skills are comprised of speaking and listening skills by looking at respondents’ English-speaking

practices as another productive skill in EMI classrooms. If the students’ perceptions are in the range of ‘agree’ to

‘strongly agree’, that means students do not have problems in their interactional skills. Table 3 shows that 70.4% (51.6%

+ 18.8%) of respondents prefer to deliver English oral presentations. However, 52.4% (17.2% + 35.2%) of them agree

that English is not their first choice when they come to have peer interaction in group work. The majority of respondents

(84.4% = 50.8% + 33.6%) agree with using English as the sole language of communication with instructors.

Additionally, most of the respondents perceive themselves at the range slightly disagree to agree (77.3% = 27.3% +

50.0%) in asking and answering questions in English during class time. Although a total of 76.6 percent (25.0% +

51.6%) of respondents claim that they cannot express themselves better in English than in their mother tongue, but they

do not ask questions in their mother tongue (80.4% = 53.1% + 27.3%). There is 75 percent (60.2% + 14.8%) of them

disagree English is an obstacle to delivering proper answers to assigned questions. More than half of them (55.5% =

33.6% + 21.9%) support using English while 44.5 percent (10.9% + 33.6%) of them prefer to use their mother tongue

if it is allowed. The majority of respondents (63% = 44.35% + 18.65%) agree as a total to the constructs of interactional

skills. It can be concluded that using English in EMI courses is compulsory as one of the key academic achievements

in the teaching and learning process.

2: 4 103

KKU Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (Graduate Studies) Vol. 9 No.: 2May-August 2021

Table 3 Interactional skills

Speaking and listening skills

Disagree

Slightly

Disagree

Agree

Strongly

Agree

Mean

Score

S.D.

I prefer giving oral presentations in

English.

10 (7.8)

28 (21.9)

66 (51.6)

24 (18.8)

2.81

0.830

In group work, I interact with peers in

English only.

22 (17.2)

45 (35.2)

47 (36.7)

14 (10.9)

2.41

0.901

In class, I interact with instructors in

English only.

0 (0.0)

20 (15.6)

65 (50.8)

43 (33.6)

3.18

0.681

In class, I find no difficulty answering

and asking questions in English.

7 (5.5)

35 (27.3)

64 (50.0)

22 (17.2)

2.79

0.790

I express myself better in English than

in my mother tongue.

32 (25.0)

66 (51.6)

24 (18.8)

6 (4.7)

2.03

0.793

In class, I do not ask questions in my

mother tongue.

5 (3.9)

20 (15.6)

68 (53.1)

35 (27.3)

3.04

0.767

I do not feel that English is an obstacle

to delivering proper answers to

assigned questions.

4 (3.1)

28 (21.9)

77 (60.2)

19 (14.8)

2.87

0.692

If the use of the mother tongue was

allowed, I would not use it in classroom

daily interaction.

14 (10.9)

43 (33.6)

43 (33.6)

28 (21.9)

2.66

0.941

Collective ‘Speaking and listening’

construct

94 (9.18)

285

(27.84)

454

(44.35)

191

(18.65)

2.72

0.370

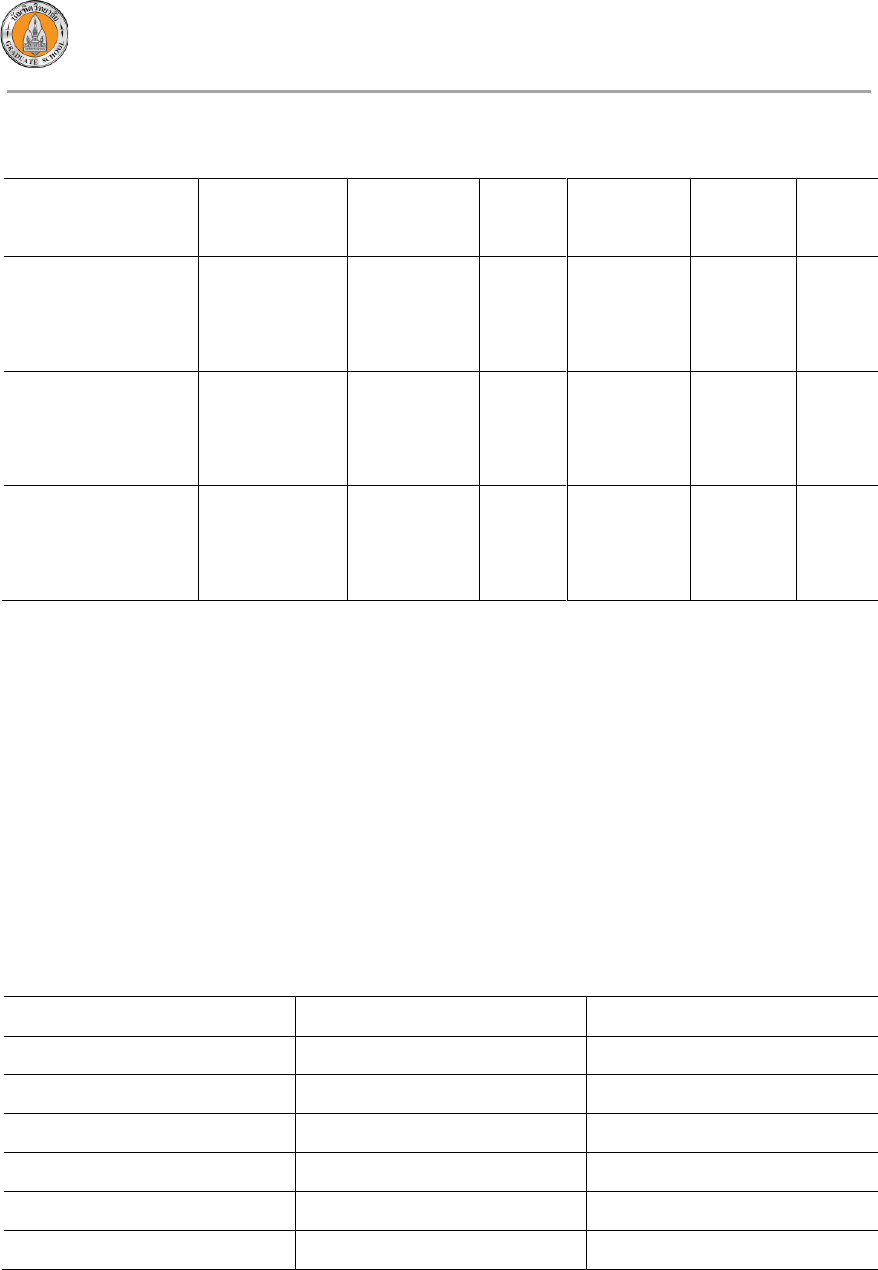

Inferential results of differences between English academic skills and demographic backgrounds

Respondents’ demographic backgrounds, namely nationality, study program, and academic year of study

were taken into account. As indicated in Table 4, there was a significant effect of respondents’ demographic

backgrounds on their writing and reading skills at the p<.01 level for three conditions [F(17, 110) = 6.871, p = 0.00]

and [F(17, 110) = 13.754, p = 0.00] respectively. However, there was not a significant effect of respondents’

demographic backgrounds on their interactional skills.

2: 4 104

KKU Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (Graduate Studies) Vol. 9 No.: 2May-August 2021

Table 4 One-way ANOVA results between English academic skills and respondents’ demographic background

Sum of

Square

df

Mean

square

F

p

Writing skills

Between Group

44.457

110

.404

6.871

.000

Within Groups

1.000

17

.059

Total

45.457

127

Reading skills

Between Group

88.997

110

.809

13.754

.000

Within Groups

1.000

17

.059

Total

89.997

127

Interactional skills

Between Group

17.417

110

.158

Within Groups

.000

17

.000

Total

17.417

127

**p<.01

Inter-correlations between academic language skills

Table 5 shows [32]’s interpretation of the correlation coefficient which was used by the researcher to assess

the inter-correlations between academic language skills, namely writing, reading, and interactional skills. Table 6 shows

that significant inter-correlations (p<.01), with a strength of ‘moderate to substantial’ to ‘substantial to very strong’

association and positive.

Table 5 Designation of the strength of association based on the size of correlation coefficients

Strength of association

Negative

Positive

Low to moderate

-0.29 till -0.10

0.10 till 0.29

Moderate to substantial

-0.49 till -0.30

0.30 till 0.49

Substantial to very strong

-0.69 till -0.50

0.50 till 0.69

Very strong

-0.89 till -0.70

0.70 till 0.89

Near perfect

-0.99 till -0.90

0.90 till 0.99

Perfect relationship

-1.00

1.00

Pearson correlation results showed that writing skills are significant, positive, and substantial to very strongly

correlated with reading skills (r = .564, p<.01). The second strongest strength of correlation between reading skills and

interactional skills (r = .490; p<.01) showed a moderate to a substantial association. Moreover, the result indicated that

writing skills had the weakest association strength with interactional skills (r = .454; p<.01). Therefore, to a substantial

2: 4 105

KKU Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (Graduate Studies) Vol. 9 No.: 2May-August 2021

to a strong extent, an increase in writing skills is associated with an increase in respondents’ reading skills. However,

results also indicated that writing as well as, reading skills of respondents, is moderate to substantial correlated with

interactional skills.

Table 6 Inter-correlation coefficient between English academic skills

English academic skills

Writing skills

Reading skills

Interactional skills

Writing skills

1.00

0.564**

0.454**

Reading skills

0.564**

1.00

0.490**

Interactional skills

0.454**

0.490**

1.00

**p<.01

Discussion and Conclusions

The results showed that most of the higher education students recognize the value of EMI while they are

studying in EMI courses. Even though they are encountering some problems in their learning process and sometimes

they want to use their mother tongues in certain circumstances. According to [28], the focus of the EMI program in

higher education institutions is content, thus language learning objectives are secondary matters. However, results

indicated that students in this study expect that, through participating in the EMI program, their English language skills

will develop tremendously. Moreover, students perceived positively toward EMI can reduce problems for them to

comprehend in their learning. This is reflected in the results as students gave the high mean scores in these three learning

activities such as they read textbooks and course materials to expand their English vocabulary (mean score = 3.31),

they interact with instructors only in English language (mean score = 3.18), and they do not ask questions in their

mother tongue. The results are corresponding to the previous studies [3, 4, 12]. The results imply that students believe

that EMI can provide the specific outcomes associated with their specific learning behavior [6].

On the other hand, results revealed that there is a high percentage of students who are still relying on their

mother tongues throughout their learning. For example, students found themselves better in their mother tongues than

in English (76.6%) and they will use their mother tongues in classroom daily interaction if they are allowed to do so

(44.5%). Besides, results showed that interactional skills are the most challenging skill which contradicting [33]’s

result. [33] found that writing skill was the most challenging skill. Moreover, ANOVA analysis showed that there are

significant differences between writing and reading skills, except interactional skills to students’ demographic

backgrounds. This means that students’ demographic backgrounds such as nationality, program, the academic year of

their study have no positive impact on interactional skills. As higher education institutions in Thailand context strive

to become globally competitive, internationalization and EMI seem to go concurrently. However, true internalization

should take into consideration of the English academic skills of higher education students to make sure that they are

provided with the necessary support to study through the medium of English [34].

2: 4 106

KKU Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (Graduate Studies) Vol. 9 No.: 2May-August 2021

Pearson correlation analysis was used to ascertain the correlation between the three English academic skills,

namely writing, reading, and interactional skills. Although results showed that all English academic skills are correlated

significantly between themselves but writing skills are the most important skills as its impacts on reading skills (r =

.564) and interactional skills (r = .454) at a significant level as 0.01. In this line of reasoning, results imply that the

more instructors focus on improving students’ writing skills, the greater there is likely to be an impact on their reading

and speaking.

In conclusion, current EMI courses, specifically its impacts on students’ progress in English academic skills,

classroom activities, and practices have to take into account. This is because students cannot learn complicated English-

medium content without an appropriate level of English language proficiency. EMI courses expect a higher language

level from students so that they can acquire content completely with no difficulties. Therefore, the researcher would

like to suggest to Thailand higher education institutions to well-designed language placement tests that can evaluate

students capable of being taught in an EMI course setting. Hence, students will be linguistically prepared for the EMI

courses and also may lead to a comparative homogeneous classroom. Furthermore, some preparatory English language

courses, for example, English for Academic Purposes (EAP) or ESP, provide to students who are at low proficient

English language before EMI courses commerce. These courses not only psychologically prepare students to attend

EMI courses but also assist them to achieve an appropriate level of English proficiency [28].

The ultimate contribution of this paper is to investigate closely students’ perceptions of EMI implementation

so that future instructors can modify the realistic way to implement EMI courses. Hence, this will help students to

become more successful learners in the short term, and make them relevant in the global job market in the long term.

Finally, the results allow important implications for implementing EMI courses in Thailand contexts where a low level

of English proficiency may be a barrier. Subsequently, it is suggested that EMI courses have to be tailored to students’

needs based on the collaboration of subject and language instructors or specialists.

Acknowledgments

This research has been supported by the Khon Kaen University International College Research Grant. Grant

number: No 01 F20

References

1. Macaro E, Curle S, Pun J, An J, Dearden J. A systematic review of English medium instruction in higher

education. Language Teaching. 2018; 51(1): 36-76.

2. Wächter B, Maiworm F. English-taught programs in European higher education: The state of play in 2014. In

ACA papers on international cooperation in education. 2014.

3. Galloway N, Ruegg R. The provision of student support on English medium instruction programs in Japan and

China. Journal of English for Academic Purposes. 2020; 45: 1-14.

2: 4 107

KKU Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (Graduate Studies) Vol. 9 No.: 2May-August 2021

4. Hengsadeekul C, Hengsadeekul T, Koul R, Kaewkuekool S. English as a medium of instruction in Thai

universities: A review of literature. Selected Topics in Education and Educational Technology. [Internet]. [Cited

2020, May 8]. Available from: file:///G:/English%20as%20Medium%20of%20Instruction/

14eaec60d451073cb724e9d62f52ab897f75.pdf

5. Commission on Higher Education. Study in Thailand 2008-2009. Bangkok: Bureau of International Cooperation

Strategy; 2008.

6. Galloway N. How effective is English as a medium of instruction (EMI)? [Internet]. [Cited 2020, May 7].

Available from: https://www.britishcouncil.org/voices-magazine/how-effective-english-medium-instruction-emi

7. Suntornsawet J. Problematic phonological features of foreign accented English pronunciation as threats to

international intelligibility: Thai EIL pronunciation core. The Journal of English as an International Language.

2019; 14(2): 72-93.

8. Jufri Y, Mantasiah R. The interference of first foreign language (German) in the acquisition of second language

(English) by Indonesian learner. The Asian EFL Journal. 2019; 23(6.3): 27-41.

9. Cai J. College English Education: A return from GE to EAP. Foreign Languages and Their Teaching. 2014;

274(1): 9-14.

10. Jiang L, Zhang LJ, May, S. Implementing English-medium instruction (EMI) in China: Teachers’ practices and

perceptions, and students’ learning motivation and needs. International Journal of Bilingual Education and

Bilingualism. 2016; 1-13. DOI: 10.1080/13670050.2016.123166

11. Bunwirat N. English language teaching in AEC era: A case study of universities in the upper northern region of

Thailand. Far Eastern University Journal. 2017; 11(2): 282-293.

12. Bunwirat N, Chuaphalakit K. A case study of English teachers’ perception toward the significance of English in

ASEAN. In Proceedings of the 38

th

National Graduate Research Conference: Graduate research toward

globalization. 2016; 3(1): 29-37. Phitsanulok, Thailand: The Graduate School, Naresuan University.

13. Barbin RRF, Nicholls PH. Embracing an ASEAN Economic Community: Are Thai students ready for the

transition? AU-GSB e-Journal. 2013; 6(2): 3-10.

14. Choomthong D. Preparing Thai students’ English for the ASEAN Economic Community: Some pedagogical

implications and trends. Language Education and Acquisition Research Network (LEARN) Journal. 2014; 7(1):

45-57.

15. Deerajviset P. The ASEAN Community 2015 and English language teaching in Thailand. Journal of Humanities

and Social Sciences. 2014; 10(2): 39-75.

16. Phantharakphong P, Sudathip P, Tang KN. The relationship between reading skills and English proficiency of

higher education students: Using online practice program. Asian EFL Journal. 2019; 23(3): 80-103.

17. Pyakurel S. ASEAN Economic Community and its effects on university education: A case study of skill

verification by the means of professional certification examination. Unpublished master’s thesis. 2014; Bangkok

University, Thailand.

2: 4 108

KKU Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (Graduate Studies) Vol. 9 No.: 2May-August 2021

18. Bancha W. Problems in teaching and learning English at the Faculty of International Studies, Prince of Songkla

University, Phuket. Unpublished Ph.D dissertation. 2010; Prince of Songkla University, Thailand.

19. Chapple J. Teaching in English is not necessarily the teaching of English. International Education Studies. 2015;

8(3): 1-13.

20. Shuib M. English as a medium of instruction in higher education. [Internet]. [Cited 2020, August 21]. Available

from https://medium.com/@munirshuib08/english-as-a-medium-of-instruction-in-higher-education-

f701940b07b6

21. Grabe W. Current development in second language reading research. TESOL Quarterly. 1991; 25(3): 375-406.

22. Grabe W, Kaplan RB. The writing course. In Bardovi-Harlig and Hartford, B. Beyond methods: Components of

second teacher education. 1997; 172-197.

23. Kim H, Krashen S. Why don’t language acquirers take advantage of the power of reading? TESOL Quarterly.

1997; 6(3): 26-29.

24. Lipson MY, Wixson KK. An interactive view of reading and writing. Addison-Wesley: Educational Publishers.

1997.

25. Oxford RL, Scarcella RC. Second language vocabulary learning among adults: State of the Art in Vocabulary

Instruction. 1994; 22(2): 231-243.

26. Madileng MM. English as a medium of instruction: The relationship between motivation and English second

language proficiency. Unpublished Master ‘s thesis. 2007; University of South Africa, South Africa.

27. Lei J, Hu GW. Is English-medium instruction effective in improving Chinese undergraduate students’ English

competence? International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching. June 2014; 52(2): 99-126.

DOI: 10.1515Iral.2014.0005

28. Wanphet P, & Tantawy, N. Effectiveness of English as a medium of instruction in the UAE: Perspectives and

outcomes from the instructors and students of University Science Courses. Educational Research for Policy and

Practice. 2018; 17(2): 145-172.

29. Galloway N, Kriukow J, Numajiri T. Internationalization higher education and the growing demand for English:

An investigation into the English medium of instruction (EMI) movement in China and Japan. The British

Council; 2017.

30. Wang ZY. Investigating ESP teaching for English majors in Technological Institutions. Contemporary Foreign

Languages Studies. 2015; 11: 50-53.

31. Babbie E. The basic of social research. 6th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning; 2014.

32. De Vaus D. Survey in social research (6

th

ed.). England, UK: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group; 2013.

33. Evans S, Morrison B. Meeting the challenges of English-medium higher education: The first-year experience in

Hong Kong. English for Specific Purposes. 2011; 30(3): 198-208.

34. Macaro E, Curle S, Pun J, An J, Derden J. A systematic review of English medium instruction in higher

education. Language Teaching. 2018; 51(1): 36-76.